- Home

- J. C. Carleson

Placebo Junkies Page 19

Placebo Junkies Read online

Page 19

Every story needs a hero.

Chapter 40

All those I woke up in someone else’s body stories I’ve read or watched over the years, and not one of them does fuck all to help me now.

I don’t care if it’s Kafka or yet another Freaky Friday remake—they all use pretty much the same basic formula, amiright? Person wakes up, checks their shit out in the mirror, and is all ohmygawd, holy shit, wtf for a while. Then, later on, they get used to their new body and play around and have fun with it for a while, like, look at me, I’m a big hairy cockroach climbing up the walls, wheee! Little girls check out their new grown-up boobs, little boys have fun learning to shave their overnight-adult faces, whatever.

You can practically hear the fledgling screenwriters pitching their film agents on their latest version, their spin on a spin on a spin that’s been done a hundred times: Who hasn’t occasionally wanted to wake up as someone else?

I’ve certainly wanted to wake up as someone else. Of course I have. But the whole goddamn point of that fantasy is to wake up in someone else’s body, with someone else’s life. Instead, I wake up with the same shitty life, the same scar-blasted, toxic waste dump of a body, and someone else’s memories layered on top of mine. I’m me, but not me. I’m doubled down—all of my problems and hang-ups and deficiencies multiplied by Fact and by Fiction. I’m someone’s sick-joke version of “cured”; I’m me to the power of fucked.

I’m not seeing the potential for slapstick antics here.

I think the film rights to this one will remain safely mine.

Sunlight filtering in through safety glass and the sound of a lunatic gargling somewhere down the hall jolt me out of the stupor that has replaced sleep, but I don’t get up just yet. There are too many cobwebs and fissures still crisscrossing my thoughts to be able to face the day. So I lie in my bed, which isn’t really my bed, and untwist the snarled braid I seem to have created out of the details of my life.

Fact: My name. Several people confirmed it last night, including one of the many nurses who fade in and out of my field of vision like pill-pushing ghosts, and Jameson, whose clothing I now realize matches the uniforms worn by several other key-ring-wielding men I’ve seen wandering around—men who fall below the nurses in the pecking order, but above the cleaning staff. Orderlies, maybe, though do they still use that word? It sounds too old-timey, so I’m sure it’s been replaced by something stiff and modern and ridiculous: Psychiatric Sanitation Engineer, or Certified Cranial Technician.

The nurses are familiar, too; I’ve seen them all before. But back on the flip side of this little breakdown, this total mental meltdown of mine, they were lab administrators and research assistants.

Here on this side they don’t ask for my consent. Here, I’m supposed to hand over my veins and swallow their pills for free. Here, they think they’re in charge.

And yet, here’s another fact: there is money under my mattress. (Un)grand tally: two hundred and thirty-one dollars. Hardly enough for the trip of a lifetime. Does Castillo Finisterre even exist? Add that one to the mountain of questions already towering over me.

Also under the mattress: hundreds of other pieces of paper, all folded with maniacal precision into rectangles the size of dollar bills. Sad, crazy counterfeits that make my today-face burn with shame. The pathetic currency of my delusional mind. But this discovery is almost comical considering what’s also under the mattress: a shitload of pills. They’re faded and crusty, like they were held in someone’s mouth just long enough to start to dissolve.

Someone’s mouth. How delightfully passive of me, no? Just thinking about it, I can feel the sensation of a smoothly-coated capsule rolling under my tongue. I taste the memory of that first bitter release of what’s inside, and I reflexively start to push the taste out of my mouth. My mouth.

If there was ever a time not to be passive, it’s now. So … Fact: those are clearly my pills, which I clearly spit out of my mouth. I have no conscious memory of doing so, just the muscle memories of ingrained habits. I don’t know why I refused this hidden cache of medicines, but there must have been a good reason. Which brings up yet another question, this one with some urgency: who can I trust? Doctors and nurses proffering questionable cures, or my (less than reliable) self?

Neither option holds much appeal.

I shove my hand under the mattress and pull out another handful of folded pages, flicking away two crusty capsules that stick to my sleeve like burrs. My Madwoman’s Monopoly Money mostly consists of tissues, random flyers, and articles torn from magazines. My fortune is a practical joke, played on me, by me. Perhaps there’s comedic value to my story yet.

Nope. Not funny, Audie. Not funny at all.

Fortunately, among the useless trash are dozens of identical brochures bearing glossy and copyedited answers.

Because if it’s in writing, it must be true. (And if you believe that, then have I got some great drugs to sell you!)

I unfold one of the pamphlets with shaking hands and read.

Facts, as spelled out in tactfully euphemistic jargon: “The Cedar Hill Center for Transitional Living provides residential psychiatric care for adults and adolescents with persistent mental illness. Various levels of intensity are offered in our apartment-style community, which is conveniently located on the grounds of a top-ranked, university-based hospital system, thereby ensuring that residents have access to state-of-the-art treatments and facilities.”

Whoever designed the brochure chose a mint-green tree motif for the cover, which makes zero sense at all, since what the hell do trees have to do with crazy people? Personally, I would’ve gone for an ice-pick design. “Cedar Hill Psych Ward: Not just for lobotomies anymore.”

Fact: I am crazy. Crazy crazy crazy crazy crazy. Insane in the membrane. Out to lunch. Cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs, wack job, nutso, loony tunes. Fucked in the head.

Sick.

Or so they say.

It takes a very long time before I can convince myself to get out of bed.

When I finally do, I’m relieved to find that my home today is much the same as it was yesterday. Yesterday, back when I was still … on the reality-is-optional channel, shall we say? Not that I’m not anymore, just, I don’t know. Something has cracked. Something I took, something I stopped taking, something Dougie said, something I did, I don’t know what, just something has changed and now I’m seeing certain things I didn’t before. And not seeing certain other things that I used to see.

Eeny, meeny, miney, moe. Audie’s mind catches up slow.

The truth has now achieved critical mass in my mind, and it’s forcing out all the beautiful, happy stories. My fantasy world is a smoldering wasteland.

Fiction: Dylan, whispering (lies) in my ear. Arms around me, holding me, keeping me centered, his (stranger’s) flesh on my flesh, keeping me (in)sane. His whispered (lies) promises, we’ll get through this together, baby.

Liar, liar, brain’s on fire.

I can’t deal with this particular crack in my brain right now, so I seal it up. It’s a temporary fix at best, but it allows me to get up and stumble around my half-familiar world.

The apartment is almost the same as yesterday—same curtains, same toaster, same couch. It’s just smaller than before; a twee miniaturization of a real apartment. Kitchen(ette). (Mini) fridge. A faux home—a dollhouse for the institutionalized set.

I think back to that day I woke up in the alley, the way everything looked huge for a few hours. Lilliputian effect, they called it. Today I’m experiencing the opposite. Today, my world has shrunk.

Reality: a most unwelcome side effect.

Different versions of events continue to unfold like origami. The Professor walked me home that day.

Zzzzzzzap.

No, Dr. O’Brien walked me home that day.

crazy stupid crazy stupid crazy stupid

secon

d verse, same as the first, a little bit louder, a little bit worse

I stare at the door to Charlotte’s room. She was real, I’m almost certain. My thoughts about her have more heft, somehow. But … is it possible that I imagined her death? Maybe it’s just a part of this whole fucked-up, delusional whatever it is that’s going on in my head. A fight between friends that my smoke-and-mirror brain morphed into a tragedy? For a second my heart races with hope that one thing, just this one thing, might actually turn out in my favor, and that Charlotte may actually be alive. But then I open the door. It’s a vacant room, the mirror image of mine—utterly anonymous with its institutional, bolted-down furniture and paste-colored walls. Anyone could have lived here. No one could have lived here.

I close the door to the empty room and try to find solace in the fact that at least now I know what I don’t know.

I fail to find solace in this fact.

It turns out that ignorance is not, in fact, bliss. Ignorance is a hole in the head and a knife through the heart. Ignorance is a terrifying void too quickly filled with Styrofoam facts and junk-food hopes.

Outside my apartment, which is not, of course, actually my apartment, the same but different trend continues. I explore the alternate universe of my shrunken world, walking through hallways that just yesterday were city-blocks long, down a stairway that used to be an alley, and across a small, grassy quad that used to be the neighborhood park. I keep my head down in order to avoid conversation with any of the quasi-familiar faces that float by.

I’m not ready for any more reality at the moment. I’m already at a toxic saturation level; I’m this close to overdosing on the truth.

But I change my mind when I see Scratch sitting on a bench. He’s revolting as ever, but he’s also someone I know and remember—for some reason he seems to straddle the gap between my delusions and my reality. Plus, he might be able to help me sort out the whole Charlotte business, which is as confusing as ever.

Scratch. Good old Scratch.

Except it turns out that today’s version of Scratch is not quite the same as the version in my recent memories.

How did I not see it before? Was I so fixated on his rashes and boils that I never even noticed his eyes—the way they’re focused so intently on something just out of range of everyone else’s vision? How did I miss the tics and twitches?

“Hey, Audie,” he says as I sit down next to him. “How’s Dylan?” His voice is sharp and mocking.

I jump up from the bench and stare at him. The scabby little fucker is grinning at me. A teasing, toying grin. So this is how it is? I’m a joke around here, laughed at even by the likes of this pus-pocked fool? I wonder if I’m at the bottom of some unwritten psychiatric pecking order: a crazy person who doesn’t know she’s crazy.

Zzzzzzzap.

Make that: a crazy person who didn’t know. I walk away from Scratch as fast as I can without calling attention to myself, not feeling the least bit elevated by my newfound knowledge.

Chapter 41

Apparently, I fall into one of the more lenient of the “various levels of intensity” described in the Cedar Hill Center’s brochure, because no one tries to stop me as I explore the facility further. Doors open freely, alarms fail to sound.

I start to feel like a character in a children’s book: Audie goes in. Audie goes out. See Audie go upstairs? Go downstairs, Audie, go down!

I test my limits here. I test her limits there. I am (apparently) allowed to go damn near anywhere.

This seems like very bad judgment on their part.

How fucking crazy do you have to be before they actually lock you up?

Only once is my freedom challenged. Several steps out one set of doors that open to within sprinting distance of the outside world—an unfenced, unchained outside world, no less—a frizzy-haired nurse wearing mismatched pastel scrubs chases me down. I’m sure I’ve been caught, and I’m about to be reeled back inside, but she only wants me to sign out if I’m planning to leave the grounds at any point. She tsk-tsks mildly and hands the clipboard back to me when she sees that I’ve signed as Charlotte.

It surprises me, too, that I did that. Habit, I guess.

Even with my freedom grantedI don’t roam far, and I don’t attempt to leave the grounds just yet. A clock on the wall tells me I only have another hour to kill before meeting Jameson.

As I explore, I take note of the studious demedicalization of certain areas of the facility. Prefabricated tranquility abounds, from the carefully curated art studio (nary a decapitation nor animate phallus are depicted in any of the artwork hanging on the wall) to the obsessively weed-free community garden, and right down to the belligerently peaceful scent of the eucalyptus/lavender air freshener permeating the building like olfactory Haldol.

The pretense fades gradually toward the west, however—westward being the direction of the main hospital. The real hospital, that is. The one that doesn’t pretend to be anything but a hospital. The hospital not suffering from delusions, one could argue. (Sense of humor: intact, but hanging on by a thread.)

I feel more comfortable in these westward, nondelusional corridors, with their wafts of unapologetically alcohol-swab-scented air and the percussive rattles of unmuffled metal trays against unmuted metal bed rails. I peek into one room and see a young doctor irrigating a wound—and angry, open slash across the bicep of an uncomplaining man with a matted beard—and the sight actually soothes me.

I guess I prefer the kind of treatment where the pain comes up front.

It’s only when I follow a hedge-lined walkway to its end and enter the lobby of a separate building, shiny-new and clearly more modern than the others, that I encounter any real obstacles—this time in the form of a receptionist who intercepts me apologetically. She’s as wide across as three of me standing side by side, but she’s skittish as she blocks me, and when she speaks it’s in that high-pitched, saccharine-sweet voice that people save for babies, old people, and imbeciles.

“Now, Audie,” she coos. “I don’t think you have an appointment with Dr. O’Brien today. If you need to speak with him, you’ll probably be able to find him out wandering the halls, though. He has to be the most dedicated doctor I’ve ever worked with; we just love him around here. I’m sure you must know how lucky you are that he’s taken such a shine to you.”

I half expect her to reach out and pinch my cheeks, the way she’s simpering at me.

I ignore her and peer over her shoulder. The smile fades a few degrees, replaced by a tiny, nervous laugh that makes her fleshy face jiggle slightly.

It’s an impressive building. The lobby is a soaring atrium with huge glass panes angled in such a way that it almost feels like you’re standing in the middle of a well-cut diamond. Deep-set, overcushioned chairs engulf slack-faced patients in this jewel of a waiting room, many of whom are accompanied by watchful attendants, and the amplified sound of an artificial waterfall flowing through the center of the room drowns out any possibility of meaningful conversation. The lobby is ringed by offices with closed wooden doors, each bearing the name of the doctor holding court inside. I can’t be positive, since I’m standing too far away, but if I squint I think I can just make out Dr. O’Brien’s name on the third door from the left.

The first thought that jumps to mind is that old saying about people who live in glass houses. “Shouldn’t throw stones,” I whisper, making the nervous receptionist jiggle and giggle even more.

Then, as I stand there, squinting against the almost intolerably sunny brightness of the atrium, another quote comes to mind—one that fits even better. The one the Professor—Dr. O’Brien—underlined in the copy of 1984 he left for me. We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness.

Something about making this connection makes me shiver violently, and I wrap my arms around myself to quell my shaking.

My sudden(ish) movement pushes the nerv

ous receptionist too far, and she springs surprisingly fast back to her desk and picks up a phone. “Audie, dear, I’m just going to call someone to come get you. Is that okay? Hmmm, dear?” Her voice is still sugar-pitched, but her pink-painted fingernails drum a staccato beat on the desk as she waits for someone on the other end to pick up. “Just stay right where you are, okay, sweetie?”

I do as instructed. Now that she’s moved out of my way, I can see one more door, this one different from the rest. This one is metal and secure—I see both a keypad and a card reader controlling access—and instead of a fancy brass nameplate, this one bears only a small institutional plaque. White letters on a dark-green background read locked ward.

There’s no reason this should trigger anything at all in my head. I mean, the presence of a locked ward in a mental health facility is hardly surprising, but trigger something it does. One last quote—this one more clichéd, less literary, and straight out of Jameson’s mouth.

“She’s in a better place,” he’d said of Charlotte.

At the same time, it occurs to me what Jameson has never said, not once: Dead.

The receptionist is still on the phone. She’s huffing and puffing from being put on hold, as far as I can tell, and my presence has her skittish as a horse. I’m not interested in staying there any longer, though. I’ve seen enough.

I arrange my face into its most wholesome configuration—wide, smiling eyes, deferential tilt to head—and reassure her in a voice almost as syrupy as her own. “Oh, I’m okay, really. I just got my appointment dates confused. I’m such a space cadet!”

She looks at me for a long moment, then replaces the receiver. “That’s okay, honey. It’s no problem at all,” she says, but her hand stays close to the phone and her eyes follow me out the door.

Chapter 42

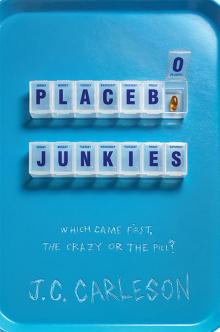

Placebo Junkies

Placebo Junkies