- Home

- J. C. Carleson

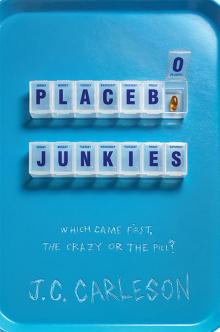

Placebo Junkies Page 15

Placebo Junkies Read online

Page 15

I turn to examine Dylan’s hairline. Now that he’s given up on getting any dark-theater action—apparently, I didn’t disguise my lack of responsiveness very well—he’s enjoying the movie and doesn’t notice me staring. Wait. Has his hairline changed, too? I could have sworn he wore his hair parted on the other side. I replay various scenes in my mind, zeroing in on his hair. Click click click, I shuffle through memories, frowning at hairline discrepancies. Finally, a pattern emerges.

Oh.

Scrutiny is the enemy of perfection.

I stretch my arm over his shoulder, pretend-casual, and ruffle my fingers through his hair to confirm what I already know. He turns his head and gives me a brief distracted kiss, then returns his eyes to the screen. I pull my hands back into my lap, ashamed of myself for only now realizing how much his treatments have thinned his hair, which used to be thick and full.

At least he’s put back some of the weight he lost.

My excessively attentive brain gloms onto any good news at all lately, since life as Charlotte has not gone as smoothly this week. Two studies busted me, shooing me out the door in disgrace. One, upon noticing discrepancies in my blood type. Charlotte: A-positive. Me: O-negative.

Make that O for oops. Definitely a big fat negative, as far as the lab was concerned.

The other study did the unthinkable: they actually looked closely at the ID I handed over. “This isn’t you,” the study coordinator said after frowning at the driver’s license for a long minute.

I wasn’t going to argue with her. I reached for the card, prepared to walk out without a scene, but she snatched it away, holding it just out of my reach. “This isn’t a game, you know,” she snapped. “You people think this is just an easy way to make a buck. Do you not understand that we’re trying to do something important here? Do you even care that pulling stunts like this, lying on your forms and swapping participants, can completely invalidate our results? You’re messing with real lives here.”

Like my life isn’t real. Like Charlotte’s wasn’t real.

We stared each other down until I finally lunged across her desk to grab Charlotte’s driver’s license and then walked out of the office.

“I’m going to warn the other offices about you,” she called after me. “I’m sending an email to the whole department. Good luck pulling off your little switcheroo in the future.”

She’s full of shit. The studies are staffed by a rotating cast of graduate students, visiting faculty, interns and technicians who have their noses buried so far into the data that they can’t be bothered with details about individual test subjects.

But still. It’s a concern. Good thing I can’t worry about it for long. I have hairlines to study.

The movie climaxes. At last, the hero’s hair comes under control; it maintains its Astroturf-y stasis and the integrity of its side part through two galactic battles, several sexy alien romps, and an interplanetary award ceremony. Two-thirds of the way through the film and someone on the production set finally started paying attention to details. Perhaps the good makers of AttentiQuil DX (patent pending!) should commence their marketing efforts in Hollywood.

Dylan wants to get something to eat, but the meds have killed my appetite. “I’ll split something with you,” I say, and he makes a face.

I recalibrate. “How about Mexican?” I say, trying to look hungry and enthusiastic.

I really hate disappointing him.

Chapter 31

Today’s post: Reflections on the (Motherfucking) Nobility of Science.

Dearest, gentle readers,

It has come to our attention that certain among us stand accused of taking advantage of what was once a process above reproach. Our crime: eking profit from science.

Foul exploiters! our critics cry out. Perverters of knowledge! Defilers of wisdom!

And what say you, wise guinea pig brethren?

What’s that? What is that faint rumbling noise I hear percolating deep within your collective bowels? A pang of conscience? A clang of doubt? A viscous kersplash of guilt, perhaps?

Could it be that you actually agree with those who seek to banish your generous and practiced bodies from these hopeful hallways of untried cures?

Ah. It appears I was mistaken, and quite so. Those were not gurgling noises of agreement. Please—the restroom is just down the hall, if you need it.

But what of the Scientific Method? our wide-eyed critics cry out. What of the dissertations? The research? The government grants?

“Data integrity,” they chant in wholesome, educated unison.

Do their protests concern you? Worry not, my cottontailed test-rabbit friends. Furrow not your furry brows. For the scientists shall not suffer. Not as long as we loyal volunteers continue to draw breath, and not as long as science beds faithfully with commerce.

Lo, we need only envision the intrepid researcher, woken in the darkest of the night by a thunderbolt of inspiration surely equal to Archimedes’s own. Eureka! this wise one cries. There must be a better way to shrink a pimple, thinks this eager and selfless soul. I shall not rest, I will not stop, until the dreams of my nine years of doctoral studies, not including two years of unpaid fellowships, are fully realized. I will find a better way! I will shrink the pimples of the world faster than anyone has before! I shall not rest until I have achieved my mission, my very goal in life.

It is you and only you, darling human subjects, who can make such dreams come true. You offer your pimples to the great gods of science. You dedicate your spotty complexions to the betterment of humanity. And all you ask in return is fair and just compensation for your vital (in the most literal sense) contribution.

For ours is the truly noble calling. Or at the very least, ours is the truly necessary one. Because theories, as you know, are cheap and plentiful.

Proof, on the other hand, is precious. (“Proof,” as defined by the FDA or the average drugstore consumer, of course.)

And that proof, dear guinea pigs, is what lies deep within our veins and tissues. So carry on, darling lab rats, confident in your role, and assured of your value.

Carry on.

Chapter 32

On the fifth and last day of my participation in the AttentiQuil DX trial my fixation du jour becomes (drum roll please): Charlotte’s tattoos. I quickly become obsessed with the circular snakes I saw inked on her back the day she died.

The only reason I think of them in the first place is because of all of the funny little doodles in her calendar. Certain things—appointments, anniversaries, reminders, who the hell knows?—she didn’t even use any words. Just a doodle next to a date and time—like that starry-eyed smiley face. I’ve figured a few of them out; it’s kind of like a twisted little puzzle game.

Want to play? Then guess the meaning of these little red circles.

tick tock tick tock tick tock

Stumped? Here’s a clue: they tend to show up roughly every twenty-eight days, usually for five days in a row.

Yes, boys and girls, you guessed it. Red dot = red period = Charlotte was having her period. She was many things, but Charlotte was definitely not subtle.

I’m a little embarrassed, then, by how long it took me to figure out the meaning of one particular symbol that appeared every Thursday evening for the last three months: a half circle, flat side up, with smaller circles poking out of it.

A pot of gold, I thought. Some kind of payday. This, naturally, piqued my interest. I won’t tell you how long I scavenged around her room, emptying her drawers, and even pawing through the pockets of the dirty clothes in her laundry basket, until I finally figured out that the pot of gold was Charlotte’s rendition of a falafel sandwich. Her way of reminding herself of the Thursday-night two-for-one special at the deli down the street.

She was many things, but Charlotte was definitely not artistically inclined.

I figured out almost all the other symbols pretty quickly. You just have to take a minute and get into a Charlotte-y frame of mind—she had kind of a tipsy, literal way of thinking, with a healthy splash of good-tempered anarchy and a firm commitment to toilet humor. Once you manage to squeeze into her thought patterns, it’s pretty easy to figure out what her doodles mean.

Except for the snakes.

They look exactly the same in her calendar as they did on her back—snakes curled into circles. The drawings show up three times over the last six months, and there’s one more next week. Wednesday afternoon at 2:00. There’s no other information—no names, no locations, no text at all.

Normally, I’d shrug it off, but the AttentiQuil won’t let me. It shackles my brain to the symbol, and won’t let my thoughts wander no matter how much they want to.

It’s annoying as hell, to be honest.

I get back at the AttentiQuil people by scrupulously listing side effects when I fill out my paperwork. I check off almost all the possible boxes: anxiety, insomnia, irritability, twitching, abdominal cramps. You name it, I report it. I have a little fun with the open-ended section at the end. “List any side effects not previously mentioned,” it says, so I do.

I write: blue urine, nighttime teeth grinding, preoccupation with other people’s follicles, compulsive ChapStick use, degenerate thoughts, pyromania, incurable laziness, and general insufferability.

And then in all caps, I write and then underline:

Someone once told me that’s the worst feedback a pharmaceutical company can get. People will tolerate all kinds of nasty side effects from their prescription medications—they’ll put up with heart palpitations and liver damage and blinding headaches every day of the week, but weight gain is the kiss of death for a new drug. That and erectile dysfunction, but I’d probably destroy my credibility if I tried to tack that one on.

The study coordinator flips through my paperwork to make sure I completed everything, and I see her wince as she looks at what I wrote. She looks pissed, but she doesn’t have a choice, so she hands me the envelope with my money. She sort of hurls it at me, actually, but I’m still Charlotte in here, so I just don’t care.

I go straight from the study to the area of the labs where the Professor tends to linger, hoping to find him. I know it’s the medication, but that snake doodle is really starting to bug me. I’m starting to feel a little obsessed, actually.

Fortunately, he’s there. He’s lurking around with his little notebook in hand, as usual. Also as usual, everyone is ignoring him.

He gets this ridiculously overjoyed look on his face when he realizes I actually want to talk to him. It almost makes you feel sorry for the guy.

“Audie!” he says. “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

I grab his notebook and pen from him, which makes him stutter and panic a bit, but I make a big point of flipping to a blank page, not reading anything he’s written, and he calms down a little.

“What is this?” I ask him, and I hand him back the notebook so he can see what I’ve drawn. “What does it mean?”

If anyone would know, it’s the Professor. It’s exactly the kind of trivia that fills the minds of people like him.

He does know. “Your sketch is a bit rough, but if I’m not mistaken, that’s the Ouroboros. A serpent devouring its own tail.”

His answer makes me even more impatient. “Okay, Ouroboros. Got it. But what does it mean?”

He sinks back into the cushiony chair he’s sitting in and strokes his beard in contentment. “I’d want to double-check my sources, of course, but I seem to recall that the symbol is Egyptian in origin. Or is it Greek?”

He talks himself through it slowly. So slowly I suspect he’s stringing out our conversation on purpose. Not that it’s much of a conversation—just him talking and talking and talking. I have to force myself to shut up and listen. It’s important that I know.

The Ouroboros symbol appears throughout history, the Professor says. Curiously universal are the words he uses. Quetzalcóatl, the Aztec serpent god, sometimes took on its looping shape. It shows up in Norse mythology. Alchemists wrote about it. Jung did, too.

It represents infinity. Continuous renewal. The joining of the opposites, creation from destruction. Blah blah blah. On this topic, at least, the Professor knows his stuff.

Maybe he knows a little too much, I start to think.

“It also makes for a helluva tattoo, don’t you think?” I ask, just to see how he responds.

But from the way he blinks and tilts his head like he’s confused about why I’d interrupt his little soliloquy with this not-particularly-deep observation, I realize he doesn’t know what I’m talking about. He doesn’t know about Charlotte’s tattoos.

I let him ramble on a little more, but I already know enough. The Ouroboros obsession box has been checked off my mental list of side effects, and I finally feel released from its grip.

“Thanks for the info,” I call over my shoulder.

The Professor, looking a little dejected about my rapid departure, frowns and waves goodbye.

Chapter 33

I go home between appointments to stash my cash under my mattress.

Yes, my mattress. Shut up.

It’s an embarrassingly obvious hiding spot, but my options are limited. All the real furniture in the apartment belongs to someone else. Everything was already here when I moved in. I don’t even know who actually owns what. The couches for example. Who bought those—Jameson or the Roommate-Formerly-Known-as-Charlotte?

And do I have any claim to whatever was Charlotte’s? Not that I even care whose crappy coffeemaker it is now, or who should be called the rightful owner of the hand towels. But it might be nice to have a sense of ownership, of permanence, for once, instead of living like a goddamn nomad for the rest of my life.

Everything I own can and has fit in the back of a cab with room to spare. A futon mattress, a set of stackable plastic organizers in lieu of a dresser, and a duffel bag full of miscellaneous crap I haven’t had the energy to toss. There are depressingly few nooks and crannies among my meager possessions, so under the mattress it is. Better than in the hands of a thief. Again.

Sadly, my hidden treasure is not growing as fast as I’d hoped. I’m so very, very close to the magic number that can make Dylan’s birthday trip happen, but two more studies turned me-as-Charlotte away this week, and everywhere I go I can feel people looking at me in all the wrong ways. The hallways are lined with tilted, turning heads and smirking, narrowed eyes.

What’s that famous quote? Sometimes paranoia’s just having all the facts? Well, I’m still sorting through the facts, but it’s starting to become obvious.

I’ve been blacklisted.

Not that there’s an actual list. My face is not displayed on wanted (or, more accurately, UNwanted) posters in back-hallway administrative offices. Blackfogged might be a more accurate description of my current status. As in, there’s a noxious, slow-moving cloud spreading misgivings about me, damply telling unflattering tales.

The money has slowed to a trickle.

Sometime’s paranoia’s just having eyes and ears.

Jameson is home in the middle of the day, smelling riper than ever. He used to be so clean.

“Aren’t you working today?” I ask him.

“What do you mean? Of course I am.” He’s jumpy, which I’d normally assume was a side effect, but I haven’t seen him leave the apartment all week. Whatever’s making him anxious isn’t chemical in nature.

“So help me out, then.” And when he makes a face, “C’mon, Jameson. You always have some kind of hustle going on. Can’t you hook me up with anything? I need to make some quick cash.”

“No.” He gives me a weird look, takes a deep breath. “But hey, can we talk?” He waits until I get closer, until he can be sure I’m paying attention. I’

ve stopped taking the AttentiQuil, so, admittedly, there’s room for doubt.

“Audie,” he finally says, “I like you.”

Shitballs. Where is this coming from? I’ve never gotten that vibe from him, like, ever, and it’s pretty much the last thing I need to deal with right now. I’m about to give him that whole stupid I like you too but speech when he shakes his head.

“No. Jesus, no. Not like that. You’re a freaking kid. Plus—” He stops, then shakes his head again like he’s trying to get rid of a disturbing image. “I just mean that I like you as a person, and I worry about you. Maybe you shouldn’t be doing this stuff to yourself anymore. You’re too smart for this place, for this shit. You need to get out of here, get a real life.” He looks away, his face turning pink. “Get out of here before you end up like Charlotte.”

He keeps talking, but I’m fixated on his fingernails—long on the left hand, chewed to the quick on the right—and I’m too focused on his jagged cuticles to listen to whatever he’s saying. I may have stopped taking the ADD pills two days ago, but I’m still getting little burst effects.

Little solar flares of temper, too. Like now.

“Okay, got it,” I say, sarcastic as hell. “You feel guilty. Guess what? So do I. It turns out that none of us had Charlotte’s back when she needed us. But last I checked nobody takes guilt in lieu of cash, so thanks a lot for all your help. Forgive the fuck out of me for even asking , since you obviously don’t want to lift a finger. Just don’t blame me if next month’s rent is late.” I’m about to walk away when he raises both hands into the air in defeat.

“Okay, okay,” he says. Shakes his head like I’m a lost cause. “Forget I said anything.” He sighs, and I can smell his stale breath from three feet away. “Give me a day or two. I may be able to find you something. But in exchange, all I ask is that you think about something.” He pauses until I give him a sharp, angry nod. “I just want you to think about the fact that I knew Charlotte for five years. I watched her survive five years of this shit. It’s not really surprising, what happened to her, when you think about it like that.”

Placebo Junkies

Placebo Junkies